GAS: Can you describe the moment, event, or thought in which you understood for yourself what language is, and how it can be shaped, and that you yourself could shape it, and that you desired to? Maybe more than a single point.

LENNART: That discovery was apparently largely intuitive, self-taught, and matter-of-fact. And on-going. I’m told I came into the world with swelling imagination and quick learning. By the age of 4, I was reading the Sunday paper’s comic strips, and understanding that the relationship between the drawings and the words formed a specific story; somewhere in that year, though I don’t remember what prompted me, I wrote my first sentence-long story: “gee i want to be a g-man.” At 6, going by the date on the yellowed, lined paper my father gave me a few years ago, I wrote a 2-page story about a bird, complete with illustrations. At 8, my mother and 3rd grade teacher battled with the local library to let me read from the “grown-up” shelves — Poe, Michener, and Heinlein come first to mind — which lead to writing short stories and mentally outlining novels by 10. I found Sandburg’s poetry by 15, which triggered my exploration of words as images instead of descriptors. I’m 74 now, my work has been in print since I was 17, and I’m still finding new ways to combine words into new shapes.

GAS: As a lover of ekphrastic work, I appreciate the skill with which you weave your inspiration. What are some of your favorite ekphrastic works by other poets?

LENNRT: I’m one of those weird (in a nice way) people who don’t think in terms of favorites, whatever the topic of conversation. Even in the narrow terms of this question, my interests and delights are omnivorous and eclectic. Aside from the poetry I’ve devoured over the past 60+ years, in just the last dozen years I’ve attended hundreds of readings, a fair share of them with at least one very good ekphrastic piece. The Illinois State Poetry Society works regularly with groups of artists, writing poems to their visual art (and, at least once that I know of, writing poems to inspire them to create art), which adds scores of poems to the “I love all these words” category. Perhaps it’s an over-generalization, but no two poets write the same poems, good or bad, even to the same subject. There’s too much good for a simple hierarchy.

GAS: Photography question: Did you, or do you still use a darkroom?

Do you think that those silvers can ever be equaled?

What cameras and why?

LENNART: I had the partial makings of a dark room in high school, but was never serious about it, perhaps because my parents were less than encouraging about my interest in photography (or my writing, for that matter).

Do I love black and white photography? Yes, but no more or less than color, form following function (and whatever, in the early years, was cheapest/available). From maybe 1960 to 1974, the majority of my work was in b&w, using over those years a Kodak roll-film point-and-shoot, an Argus C3 rangefinder, and a second-hand Ricoh twin-lens reflex.

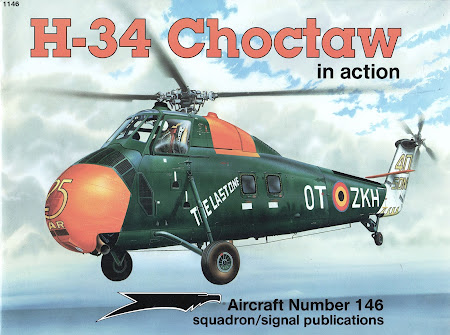

Shooting seriously as a historian documenting civil and military aviation and vehicles, I moved to color more and more out of necessity, with a couple of Olympus SLRs and a 20-box block of Kodachrome 25 always in my bag; some 7,000 images are in service museum and Smithsonian archives, and a fair number in both my books and those of several colleagues. Now, as historian and artist, I use a Nikon DSLR, and an iPhone 13 for unexpected opportunities, to shoot both b&w and color. Form still follows function, and my equipment is dictated by income.

GAS: Have you ever combined all of your arts into one piece of art?

LENNART: I’ve shot the covers for most of my poetry books, as well as cover and inside photos for several anthologies that included my writing. More to your point, I think, as single pieces of art, I’ve created a few broadsides combining my images and words, and have had some publications of my photos alongside related poems. Overall, though, I don’t write for my photos or shoot for my words. The two arts feel very separate as products of my brain and senses, though they and my other creations fuel each other.

GAS: You've been publishing since 1965! Which of your art forms were you involved in first and which was published first?

LENNART: The writer came first, followed almost simultaneously by the photographer and historian. By my early teens, all three were happening concurrently, influencing each other, and inevitably improving all of my skills as a whole. For the record, I had no writing classes as such, no photography classes at all, and no serious history classes until high school; I learned by reading, looking, and attempting.

GAS: What collaborations have you done? What are the best things about collaborations. What are the worst?

LENNART: As a photographer and fiction writer, none. As a poet, only the ISPS / Arts Guilds events mentioned above. As a historian, I’ve provided images and primary-source documents with colleagues, as they did with me, but the writing that resulted was never collaborative. I’ve also never workshopped or had beta readers, and seldom take an editor’s advice. I’m extremely possessive and protective when it comes to my arts, which probably comes from being self-taught.

GAS: Please tell us about this experience: "Navy’s Amphibious Ready Group Bravo in support of Marine Corps operations in South Vietnam during 1968 and 1969. In late 1970, he was discharged as a conscientious objector. Both events continue to influence his life and writing."

LENNART: I was a pacifist before I was a teen. When it came time to register for the draft, I applied for an exemption as a conscientious objector, which had two results: my father, who worked on Defense Department contracts, threw me out of the house, and the Draft Board turned my application down. When Lin and I talked about going to Canada, my father threatened her with bodily harm. With my draft number coming up, enlisting in the Navy was at least less likely to put me in direct combat. I served on a helicopter carrier off Danang, supporting about a thousand embarked Marines and three helicopter squadrons. Part of the support we provided consisted of several full surgical suites, a morgue, and freezers for bodies. A few months after that deployment, I was assigned to a river- and coastal-patrol ship headed for Nam at the same time that Nixon made the secret wars in Cambodia and Laos official and public. A Navy legal officer advised me that there was a process to apply for an honorable discharge as a conscientious objector, which was long and complex but resulted in a rare CO discharge in accordance with regulations. I regret my military service, and remind people who thank me for it that the war I went to was based on lies. I still have traces of PTSD, and memories I could do without, as well as poems born of them.

LENNART: It began as a passion and became, for about 25 years, a second job. I have an uncle who’s nine years older than me, and has always been more like an older brother to me. He shared his interests in all things aviation with me, as well as a broad spectrum of music and art. It helped that I lived near Chicago’s Midway and O’Hare airports for five decades before 9/11, years when access to a never-ending flow of transient aircraft was virtually unrestricted to an enthusiast with a camera.

GAS: What is your favorite form of artistic expression and why?

LENNART: All of them, each in their own way, just like my daughters and grandchildren. The sole great-grandchild has no competition at this point. Poetry, photography, history, and fiction are different in some ways, similar in others, and I set no hierarchy on the satisfaction and meaning they bring.

GAS: What is you latest project or book?

LENNART: The latest book released is Cutting a Sunbeam, a collection of ekphrastic prose poems from Kelsay Books. The next collection will be How I Went Into the Woods, which is all ekphrastic free-verse poems; Katherine James Books hasn’t given me a release date. In between, I’ll be doing my tenth annual fundraiser for St. Baldrick’s in April, which will result in a chapbook titled Poems Against Cancer 2023; keep watching Facebook for details.

My mother was legally blind in her final years. I’m in the beginning stages of converting my self-published books into large-print format through KDP, following the 2006 standards established (and largely ignored) by the National Association for the Visually Handicapped. I’d like to do audio books as well, but my vocal chords aren’t young, and professional readers aren’t in my Social Security budget.

I’m continuing to photograph aircraft and fire equipment for my colleagues as my opportunities and their needs come up. At the same time, I keep adding to my fine arts portfolio.

I’ve entered photos in a a local gallery’s February open show, and will do the same in April and June’s announced shows. I’m also working my way through the paperwork to request exhibition space at a nearby college and one of the local libraries. Photos for “ROCO 6x6x2023” (my tenth participation) have been mailed and receipt acknowledged.

Other than that, work on my artist’s Web site and the YouTube poetry readings channel are demanding attention. And there are at least three open mics on the calendar every week. Life is good, and certainly not boring.

My books are at Etsy.com/shop/VisionsWords and other online vendors. Recordings of many of my poetry and fiction readings are at YouTube.com/@lennartlundh65. A small sample of my photography is at lennart-lundh.pixels.com.

.JPG)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.JPG)